The Sweet Revolution: Exploring Sugar Replacements for a Healthier Future

Our global sugar obsession

Once, fruits, honey, and milk were the primary sugar sources. Because they occur so rarely in nature, evolution has primed our brains to love sugary foods for the quick energy they provide to our bodies. Even when refined sugar first appeared, it was something only the wealthy and powerful could afford. Now, sucrose (table sugar) and corn syrup are abundant in sugary beverages, baked goods, candy and sweets, breakfast cereals, dairy desserts, fruit juices, condiments, granola, and snack bars… the list goes on! Evolution has not equipped our bodies to cope with this amount of sugar.

The quick energy surge from consuming sugar occurs when the carbohydrates making up the sugar are broken down and released into our bloodstream. This blood sugar stimulates the crucial insulin hormone, which transports the sugar into the body’s cells, opening them up to absorb the sugar and triggering the body to store energy in fat. The rate at which a carbohydrate raises blood sugar levels is measured by its Glycemic Index (GI). A food’s Glycemic Load (GL) factors in both the ingredients’ GI and the actual amount of carbohydrates – so foods with even small amounts of high GI ingredients might have a low glycemic load. Different carbohydrates break down at different rates depending on the strength of their bindings, how they are cooked, and even the order in which foods are consumed. This makes estimating a food’s GL challenging, but it is still our most helpful metric.

Unfortunately, to comply with regulations, food labels must only include the total carbohydrates and total sugars (and sometimes total added sugars). Although this information in most cases is useful, it sometimes does not give the full picture and can be confusing for consumers looking for low-GL anti-inflammatory food because:

- Information about carbs does not disclose if they are fast or slow.

- The declared amount of sugar can be misleading and can potentially cause a health hazard if diabetic consumers over- or underdose on insulin based on what the label says. The commonly used sugar alcohol maltitol is not labeled as sugar but metabolizes into sorbitol and glucose in the body. In contrast, non-digestible sugars are declared as sugar but do not metabolize and hence have no or low effect on the blood sugar.

- Whether the sugar is added or not does not impact the body’s response.

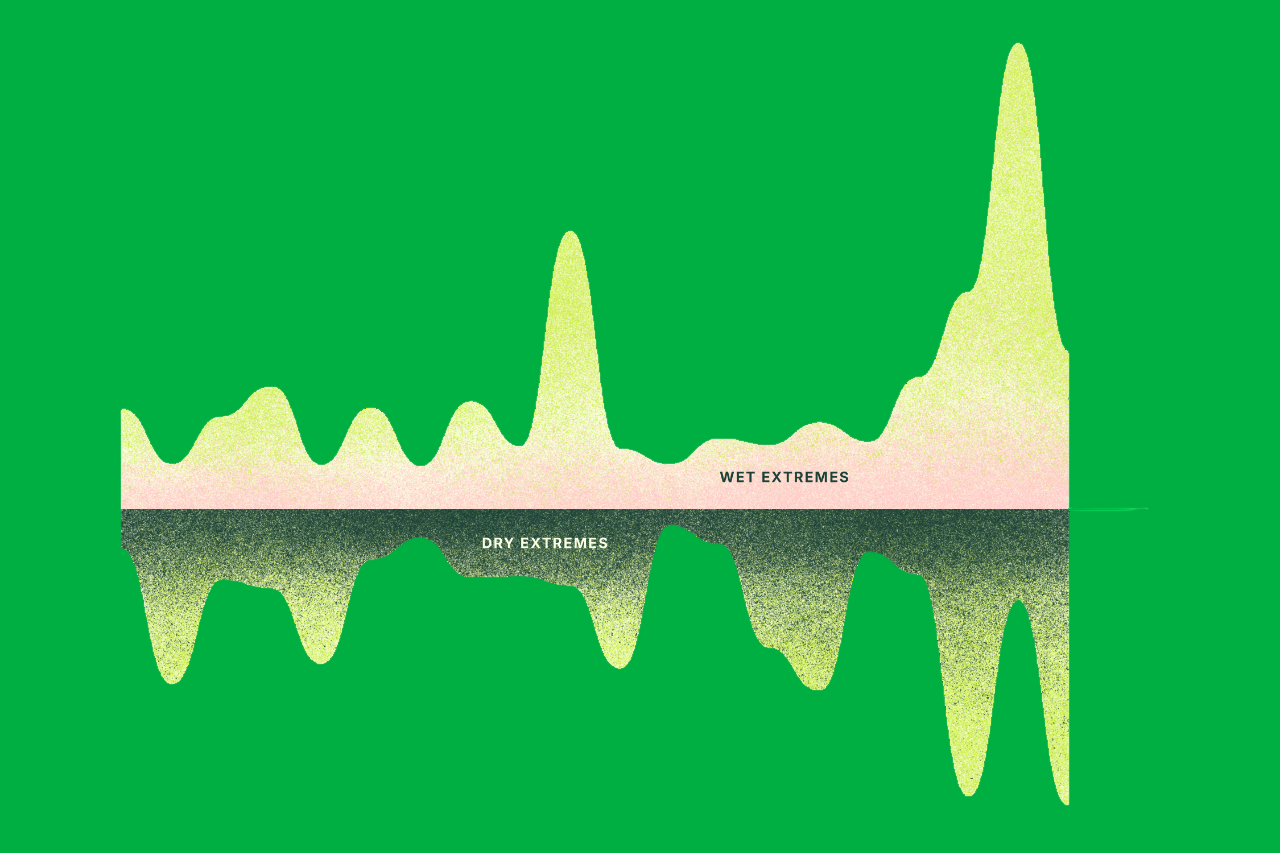

Metabolic syndrome: a massive global health problem

Sugar overconsumption is a key driver of metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that occur together and increase one's risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. These conditions include high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels, and chronic inflammation. Metabolic syndrome also is linked to obesity, inactivity, and insulin resistance.

Globally, it's estimated that around one-quarter of the adult population suffers from metabolic syndrome.

This varies by region and population, with some areas experiencing higher rates due to diet, lifestyle, and genetics. The United States has one of the highest rates of metabolic syndrome, affecting about one-third of the adult population. The Middle East, North Africa, India, China, and Latin America have seen rising rates of metabolic syndrome due to rapid urbanization, changes in diet, and decreased physical activity.

Reducing sugar consumption globally is essential to address metabolic syndrome. Yet, to make better dietary choices, consumers must work against their psychologies in a world with missing and misleading information. Our food system needs to provide consumers with more options for low-GL foods that match the taste and texture that consumers have come to crave.

Approaches for reducing sugar overconsumption

Different approaches to helping a population reduce sugar overconsumption exist. These approaches fall into two broad categories: making high-GL foods less attractive or making low-GL alternatives more attractive.

- Influencing consumer preferences: Information, health apps, or nudging (with sugar taxes or similar regulations) can influence some parts of the population to reduce sugar consumption. Mexico, the UK, France, Saudi Arabia, and other countries have sugar taxes, reducing consumption. Different studies show drops in consumption of 8-21%, with higher numbers in low-income areas. However, all food taxes, including sugar taxes, are unpopular among voters, and local producers of high-sugar foods lose revenue to neighboring countries. Denmark even revoked their sugar taxes in 2013 for these reasons.

- Changing the taste buds' perception of sweetness: The perception of sweetness is affected not only by the food's temperature and viscosity but also by some special molecules (natural flavors). For example, miraculin (derived from Synsepalum dulcificum) activates sweet receptors on the tongue, making sour foods taste sweet. In contrast, gymnemic acids (derived from Gymnema sylvestre) can temporarily suppress the taste of sweetness; the idea is that people will crave less sweets if they cannot perceive the sweet taste. Although these molecules work, the problem is that the effect lasts about 30 minutes to an hour and therefore gives the unwanted side effect of modifying the taste of everything consumed within that period.

- Replacing sugar with sweeteners: A third approach is replacing sugar with other ingredients that do not drive a blood sugar spike. Since the human brain is primed to love sugar, the challenge is creating a sweetener mix that mimics the sugar consumption experience. Besides its sweet taste, sugar has many other functions in food technology that make it hard to replace, not the least from a clean-label perspective. It acts as a natural preservative, texture modifier, fermentation substrate, flavoring and coloring agent, and bulking agent.

Sugar replacements for better-for-you indulgences

Sugar is hard to replace in food. It is cheap and has many functional properties that enhance taste and texture, preserve foods, and help with fermentation.

Fortunately, there are molecules taste sweet but do not affect our blood sugar levels. Some are artificial sweeteners made by humans, like aspartame. Others, such as rare sugars, sugar alcohols, steviol glycosides (from Stevia), and even sweet proteins, occur naturally but in small amounts. They are usually classified into intense sweeteners, several hundred times sweeter than table sugar, or bulk sweeteners that are less sweet but have other properties suitable for food production.

Different sugar replacements have different taste and texture profiles, health effects, and environmental footprints, and they can be harder or easier to work with for food producers used to sugar-based recipes. No individual sugar replacement can perfectly replace sucrose and corn syrup, so food producers must work with a mix of different sweeteners to achieve the desired properties. For example, our portfolio company Nick's uses erythritol, stevia, xylitol, soluble corn fiber, polydextrose, and sucralose as its main sweeteners in low-GL bars, ice cream, and confectionery. Sugar replacements also generally have a higher cost-in-use than sugar and HFCS, giving low-GL products a significant price disadvantage in categories where the sugar content in the original product is very high.

Despite being challenging, we believe that re-creating the sugar experience in low-GL foods is the most efficient approach to reducing sugar overconsumption and rates of metabolic syndrome. Information and nudging are important, but most consumers are not good at resisting temptation, which limits the effectiveness of this approach. Changing the taste buds’ perception of sweetness has severe adverse side effects, making major consumer adoption unlikely.

A sweet opportunity to combat sugar-related illness

Consumer adoption of low-glycemic-load (low-GL) alternatives in high-sugar categories remains gradual. However, a key proof point that low-GL alternatives can become mainstream is the success of sugar-free carbonated drinks. For instance, Coke Zero has gained significant popularity in markets such as Great Britain, Mexico, and several other countries across Europe and Latin America. Its sales have experienced double-digit growth in these regions, occasionally surpassing sales of the original Coca-Cola. This success can be attributed to effective marketing, a shift in consumer preferences towards zero-sugar options, and successful reformulations that closely match the taste of regular Coca-Cola.

Coke Zero has gained significant popularity in markets such as Great Britain, Mexico, and several other countries across Europe and Latin America.

Therefore, we anticipate that consumer demand in other categories will likely increase when low-GL products achieve a taste comparable to their sugar-laden counterparts. The rapid growth of better-for-you brands that have finally nailed the taste profile of low-GL products, Nick’s being one of them, underscores this trend.

The global market for sugar and high fructose corn syrup for human consumption alone is worth tens of billions of dollars. This giant market is dwarfed by the hundreds of billions of dollars sugar-loaded snacks generate annually. Although the post-sugar era is still in its early stages, the market size allows low-GL niche players to expand and position themselves as future market leaders, with growth accelerated by increased consumer awareness, economies of scale in sugar replacement production, and potentially supportive regulations.

Improved formulations, a wider variety of approved sugar replacements, and robust marketing strategies will drive this consumer shift, resulting in significant benefits for global health.

Are you interested in learning more about our work? Do you agree with our conclusion or think we’re missing something crucial? No matter what, we want to hear from you! Reach out to us at solvable@refood.co.